The ethics of authorship on scientific research papers

By Yinka Zevering, PhD at SciMeditor.com

3 March, 2025

All rights reserved©

Authorship on scientific research papers is the currency of an academic career: it signals your intellectual prowess and mastership of your field as well as your creativity, technical skills, and tenacity. The number of articles with your name on it, the position of your name in the authorship line, the prestige of the journals that published your papers, and the frequency of citation will dictate your long-term employment prospects, your remuneration, your promotions, the grants and industry funding you receive, and the willingness of others to collaborate with you.

This intense pressure to publish, and the rewards resulting from publication, have led to many forms of scientific research misconduct, including:

- fabricating or falsifying data;

- cherry picking data;

- plagiarism;

- using paper mills to write papers;

- using predatory journals;

- disregarding ethical guidelines around the use of human subjects in research;

- using ghostwriters;

- granting and accepting guest or gift authorship;

- crediting others without their knowledge or consent.

- failing to appropriately credit people who contributed substantially to the paper.

These unethical practices will be discussed below. Thereafter, the guidelines that promote ethical authorship allocation will be detailed.

Data falsification/fabrication

This is the most egregious of the unethical practices, because it directly contaminates the scientific literature with fake information. This can mislead the public and cause more research dollars to be spent on attempts to replicate the data. In the worst cases, it can affect medical practice and public policy and beliefs, resulting in poor patient and community outcomes. An example is the wholesale concotion of data by the anesthesiologist Scott Reuben in 1996–2008 about the use of COX2 inhibitors for pain management after surgery: his fabrication of data yielded him over 20 papers (most of which have now been retracted by the journals), led to billions of dollars in sales of COX2 inhibitors for the manufacturers, and promoted the use of potentially harmful pre/post-surgical treatment protocols that were used with millions of patients. Another example is the 1998 The Lancet paper by Wakefield and co-authors that suggested the MMR vaccine promotes autism. Wakefield was funded by lawyers of parents, some of whose children were subjects in the paper: the lawyers wanted evidence that could be used in lawsuits by the parents against vaccine manufacturers. Wakefield et al. cherry-picked and falsified data to create a paper that met the lawyers’ requirements. Although the paper was retracted by The Lancet in 2004, it elicited widespread public suspicions about vaccines that continue to affect vaccination rates and public health today.[1–3]

The problem of data fabrication/falsification is unfortunately not small: a meta-analysis of self-report surveys reported that 2% of scientists in the medical field in the US, UK, and Australia privately admit to having fabricated/falsified data at least once.[4] This is likely to be a conservative estimate.

Peer review is one of the best tools for uncovering such cases. Encouraging whistleblowing is also important. For example, the US actively supports whistleblowers by allowing them to sue on behalf of the government: the whistleblower can receive 15–30% of recovery or settlement in cases of scientific fraud involving federal funding. Moreover, public US institutions are obligated by law to protect whistleblowers.[5] This can have highly effective outcomes: for example, in 2019, Duke University in North Carolina paid US$113 million to resolve allegations of falsified research that was funded by federal grants.[6] Data audits or sleuthing with statistical methods, machine-learning, computational, and artificial intelligence tools can also detect fabricated and falsified data.[7–9] Also helpful is the nonprofit watchdog Center of Scientific Integrity and its blog platform Retraction Watch, which collects, follows, and publicly comments on cases of scientific misconduct and their outcomes, thus keeping the public informed.[10]

Plagiarism

Plagiarism may not per se impair the biomedical literature but it is intellectual theft. It is a serious breach of professional ethics that is strongly condemned throughout the publishing world. Consequently, most reputable biomedical journals employ plagiarism software. If plagiarism is detected, the journal may contact the institution of the plagiarizing author and/or relevant national bodies or professional societies. This may lead to sanctions on the plagiarizing author, including fines, being fired, and/or litigation.[11,12]

Cherry picking data

Cherry picking involves showing only the data that fit an hypothesis. In 2017, Mayo-Wilson et al. purposely demonstrated how cherry picking studies for inclusion in a meta-analysis radically changed how well the study drugs appeared to improve pain or depression.[13] Cherry picking is a questionable research practice because it misleads the reader into thinking the data are stronger than they really are. Similar questionable practices are p-hacking, salami slicing, and not publishing negative data. These practices as well as various forms of bias (e.g. sampling, selection, and confirmation bias) can often only be detected by critical review by peers who work in the same field.[14,15] For this reason, it is vital that independent research groups validate study findings before the findings are translated into medical practice. Moreover, to help detect (and prevent) bias, multiple reporting guidelines and checklists have been developed for randomized controlled trials (CONSORT) and other medical-research study types (e.g. STROBE, PRISMA, MOOSE, STARD, and SPIRIT). These guidelines are listed on the EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) network[16] and many reputable journals now advise their use when an author prepares a paper and/or insist on receiving a completed checklist at submission.

Paper mills

Paper mills are a serious threat to the integrity of the scientific-research literature. These are businesses that generate papers, often using fabricated or plagiarized data, and sell authorships to researchers. They actively engage in other fraudulent, even criminal, behavior, such as attempting to infiltrate the editorial boards of journals or tempting journal editors with lucrative payments to obtain favorable publication decisions. Their impact is increasing: a recent study suggested that 2% of scientific articles published in 2022 bore features of paper-mill productions.[17–19] Knowingly using paper mills signals an author who has had little training in basic research ethics, has little regard for them, or works in a national or institutional system that encourages the use of paper mills.

Predatory journals

These are bogus open-access journals, and like paper mills, they are also a growing problem in scientific research. They publish papers with little or no peer review in return for money in the form of article-processing charges (APC). They also generally do not employ plagiarism-detection tools and rarely require reliable evidence of ethics approval. Thus, these journals permit low-quality, fraudulent, and plagiarized papers, and papers that violate basic human rights, to enter the scientific literature.[20–22]

The problem posed by predatory journals is significant: in 2020, the firm Cabells, which maintains a list of predatory journals, reported that predatory STEM journals now outnumber reliable STEM journals. Each publishes ~50 articles per year, and 40% of the resulting 417,000 articles per annum are eventually cited.[23] The pollution of medicine by predatory journals is evidenced by a review of surgery residency applications in Canada in 2015–2018: the study showed that 3.6% of the applicants had published in predatory journals.[24] Moreover, predatory journals may have a broad financial impact, since they consume a significant amount of sparse global research funds: if one considers that the average APC of predatory journals is US$178 and these journals produce 417,000 papers per annum, that means US$74 million is given to these illegitimate journals every year.[23,25]

Predatory journals are extremely duplicitous and aggressive and can deceive honest researchers into publishing with them. Researchers who are early in their academic career are particularly vulnerable to this deception. I describe in another article on my website how to detect them.[26] However, many of the authors who publish in predatory journals do so knowing their illicit nature. This practice obviously allows these authors to misrepresent their scholarly aptitude and achieve unmerited positions and advantages, a status that has been referred to as zombie professorship.[27,28]

Ghostwriters and guest authors

Ghostwriting, and knowingly using ghostwriters, is also highly unethical. Ghostwriters are medical writers who prepare manuscripts at the behest of industry or other clients but are not given authorship. By its nature, ghostwriting is a deeply deceptive practice. Medical writers are skilled professionals who provide intellectual input along with writing expertise. Consequently, they can very significantly shape the message of the papers they write. Hiding medical-writer contributions means that the readers of the papers will be unaware of the biases and conflicts of interests of the medical writer. Moreover, it is not possible to hold a ghostwriter to account if they act unethically, such as emphasizing the merits of a drug while hiding its side effects. The secrecy also means that paper writing, which is inherently an academic skill, is falsely attributed to another author.

These issues are compounded by another unethical practice, namely, attributing the ghostwriter’s work to one or more guest authors, who have contributed little or nothing to the study and paper. Guest authors are invited to be authors because their seniority, prestigious research institute, and/or previous research lend credibility to the paper. In exchange, the guest author is paid or receives another reward, including access to industry funding. In some particularly egregious cases, guest authors have been made authors without their knowledge and consent.[29,30]

There is ample evidence that ghostwriting and guest authorship affect the integrity of medical research and can lead to the adoption of medical protocols that, on further investigation, are deleterious compared to standard protocols. For example, early studies on the use of recombinant BMP-2 for spinal fusion resulted in FDA approval but all of the articles deliberately failed to report adverse events. A subsequent investigation in 2011 by the US Senate revealed heavy involvement of ghostwriting and guest authorship that was paid for by Medtronic, the manufacturer of the product.[31] These problems also extend beyond the medical field: a recent report noted corruption of the literature due to extensive ghostwriting and guest authorship sponsored by the agrochemical giant Monsanto in relation to the safety of their herbicide Roundup.[32]

For these reasons, many stakeholders in biomedical research consider ghostwriting and guest authorship to be unacceptable practices, and numerous bodies have established guidelines to prevent it (see below).

Gift or honorary authors

A similar practice to guest authorship is gift or honorary authorship, where an author who has not contributed meaningfully to the paper is added to the authorship line. The gift author is generally a senior researcher, and the intention is to honor them and/or curry favor. Sometimes the gift author demands or expects to be an author, in which case gift authorship can be seen as coercive authorship.[33] Junior and female researchers are particularly subject to having gift/coercive authors on their papers.[34]

Gift authorship is thought to be the most common type of research fraud,[35] especially in the biomedical research field. For example, two surveys in 2023 reported that 28% of European PhD students granted gift/guest authorship to “a person in power” at least once[36] and 48% of surgeons from 21 countries reported including colleagues as gift authors for reasons of “courtesy”.[37] Moreover, a 2020 survey of 3,859 corresponding authors in 93 countries, all of whom had published articles in BMJ in 2014, reported that 74% of the respondents had published at least one paper that bore as author someone who had not contributed substantially.[38]

An extreme example of gift authorship is Yuri Struchkov, a Russian crystallographer who received an Ig Nobel prize in 1992 for being an author on 948 papers that were published between 1981–1990 (i.e. a new paper was published every 3.9 days on average). It is suspected that in exchange for authorship, Dr. Struchkov allowed researchers to use his crystallography equipment, which was difficult to access in the USSR.[39]

Gift authorship threatens research integrity for several reasons:

- it provides the gift author with unearned merit and competitive advantage;

- the gift author cannot take meaningful responsibility for the study’s findings or post-publication issues. This is important because every author is personally and professionally responsible for the content of a paper;[40]

- it can be exploitative behavior that destroys morale and corrupts junior researchers;

- it can protect fraudulent researchers from detection. An example of the latter is the case of Robert Slutsky, a clinical investigator at the University of San Diego who published prolifically. An investigation in 1986 found that 68 of his publications were likely fraudulent and that his ample granting of gift authorship to other investigators may have helped perpetuate his fraudulent behavior.[41] Given that gift authors have found themselves under suspicion of scientific fraud in cases such as that of Slutsky,[41] it is easy to see how a gift author might be unwilling to report a co-author when they suspect the co-author is engaging in unethical behavior.

Attitudes towards gift authorship are increasingly hardening. This is exemplified by the case of the department head Georg Bartsch at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria. Bartsch was an author on a 2007 paper that reported the results of a stem-cell trial that had not been approved by an ethics committee, did not inform the patients that the treatment was experimental, and may have involved forged insurance certificates.[42] Bartsch claimed he was merely a gift author on the paper, which caused the governmental agency investigating the matter to absolve him from sanction. The Lancet opposed this decision, stating in a 2008 editorial, “Using gift authorship as an excuse for not taking responsibility for research when serious flaws are uncovered... should not be tolerated. It is disappointing that honorary authorship is still regarded as a minor digression... With credit comes responsibility—always.”[40]

The widespread and continuing practice of gift authorship has led multiple bodies to explictly condemn it (see below).

Not including deserving contributors in the authorship line

Another serious authorship malpractice is not appropriately crediting significant contributors. A typical example is the supervisor coercing the junior author who conducted most of the work to relinquish authorship (or first authorship) in favor of another author or the supervisor him/herself. Such behavior often occurs in the context of a wider bullying environment created by the supervisor and/or institution and it can stymie or destroy the careers of junior authors.[43,44] Not including contributors as authors is a relatively common practice: the 2020 survey of 3,859 corresponding authors mentioned above reported that 34% of respondents had been involved in a study where a significant contributor had not been included as an author.[38]

The ubiquity of this practice has led to authorship guidelines that explictly insist that deserving contributors should be included in the authorship line (see below).

Current authorship guidelines

The many cases of scandalous research misconduct that were unveiled over the last few decades often involved authorship malpractices as well as other unethical behaviors. Consequently, there has been a chorus of calls from researchers, governing bodies, and the public for clear rules regarding authorship in scientific research. This has led to a number of guidelines and checklists, as follows.

Authorship recommedations by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)

In 1978, the editors of 12 top general medical journals (e.g. BMJ, JAMA, The Lancet, and NEJM) formed the ICMJE and produced the “Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals”. This document not only aimed to standardize manuscript preparation (e.g. reference formats), it also sought to provide a set of minimum best editorial and ethical practices in biomedical publishing.

Subsequently, the ICMJE came to contain 14 members and the Requirements were updated several times. The most recent version, entitled “Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals”, was published in 2013. These Recommendations state the following:

“authorship [should] be based on the following 4 criteria:

1. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

2. Drafting the work or reviewing it critically for important intellectual content; AND

3. Final approval of the version to be published; AND

4. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

...All those designated as authors should meet all four criteria for authorship, and all who meet the four criteria should be identified as authors. Those who do not meet all four criteria should be acknowledged... These authorship criteria are intended to reserve the status of authorship for those who deserve credit and can take responsibility for the work. ...all individuals who meet the first criterion should have the opportunity to participate in the review, drafting, and final approval of the manuscript.”[45]

The ICMJE recommendations have been widely adopted: as of 2025, nearly 18,000 journals have contacted the ICMJE to list them as journals that follow ICMJE recommendations. Notably, a 2024 study found that of 12 ICMJE journals and 82 English-language journals, 83% and 91% respectively mentioned compliance with ICMJE recommendations in the Instructions for Authors sections on their websites. While this signifies marked uptake of ICMJE recommendations, it does also indicate that even ICMJE member journals are not always fully compliant with ICMJE recommendations. Moreover, the ICMJE stipulates that it cannot verify the compliance of apparently adherent journals.[46–49] Nonetheless, the ICMJE recommendations have become the gold standard authorship guideline in biomedical research.

Authorship statement of the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME)

In 1995, WAME (pronounced "whammy") was established to represent a broader range of medical journals than the ICMJE, including small journals in resource-poor countries. It is an international, virtual, collaborative organization that is open to all editors of peer-reviewed biomedical journals. By 2017, WAME had more than 1,830 members representing more than 1,000 journals from 92 countries.[50,51] The goals of WAME include facilitating cooperation between medical journal editors, improving editorial standards, and encouraging research on medical editing practices.

In 2007, WAME produced the following statement on authorship:

“Criteria for Authorship.

- Everyone who has made substantial intellectual contributions to the study should be an author. It is dishonest to omit mention of someone who has participated in writing the manuscript (“ghost authorship”) and unfair to omit investigator who have had important engagement with other aspects of the work.

- Only individuals who have made substantial intellectual contributions should be authors. Performing technical services, translating text, identifying patients, supplying materials, or providing funding alone are not sufficient for authorship.

- It is dishonest to include authors based solely on reputation, position of authority, or friendship ("guest authorship").

- One author, often the corresponding author, should take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

- It is preferable that all authors be familiar with all aspects of the work”[49,52]

WAME is also a member of the ICMJE, and its rules on authorship align closely with those of the ICMJE. Some journals reference WAME guidelines or explictly state that they incorporate or align with WAME recommendations.[53,54] The authorship statement of WAME is seen as complementary to the ICMJE recommendations.

Authorship criteria of the Council for Science Editors (CSE)

The CSE is an international membership organization for editorial professionals who publish in the sciences. In 2009, the CSE adapted the ICMJE criteria to produce their own, more defined, authorship criteria. They are as follows:

“a “substantial contribution” is considered “intellectual” in nature. [Our] authorship criteria define an author as an individual who has contributed to the published research as follows:

- Made substantial intellectual contributions to one or more of the following:

- Conception and design (e.g., formulation of hypotheses; development of study objectives; definition of experimental, statistical, modeling, and analytical approaches)

- Acquisition of data and modeling (e.g., nonroutine fieldwork, such as adapting or developing new techniques or equipment necessary to collect essential data; nonroutine labwork, such as development of new methods or significant modification to existing methods essential to the research; literature searches; theoretical calculations; and development and application of modeling specific to the research)

- Analysis and interpretation of data

- Been involved in the writing or critical revision of the product to provide critical intellectual content

- Read and given approval of the final product being submitted for clearance and any subsequent revisions following requested revisions by editors and reviewers

... Any and all individuals who have met criteria 1, 2, and 3, independent of their rank and affiliation, should be named as authors... Authorship should not be granted to those who do not meet the criteria for authorship. Providing routine assistance, acquiring funding, general supervision of research group members, and holding positions of authority (e.g., supervisory or management positions) are not criteria for authorship... Individuals who have made a routine technical contribution (e.g., laboratory technicians, data collectors, field personnel, technical writers and editors, statisticians, or others who only perform routine data acquisition and analysis following the specific instructions of the research plan or standard operating procedure) but provide no other intellectual input to the research or scientific and technical product have not made a “substantial contribution”. To earn authorship, technical contributors must have made a substantial intellectual contribution to the research (as defined in criterion 1 above) and met the remaining two authorship criteria as well.”[55,56]

These criteria can be helpful for researchers because compared to the ICMJE recommendations, they more precisely clarify who does and does not qualify for authorship.

Author eligibility rules of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

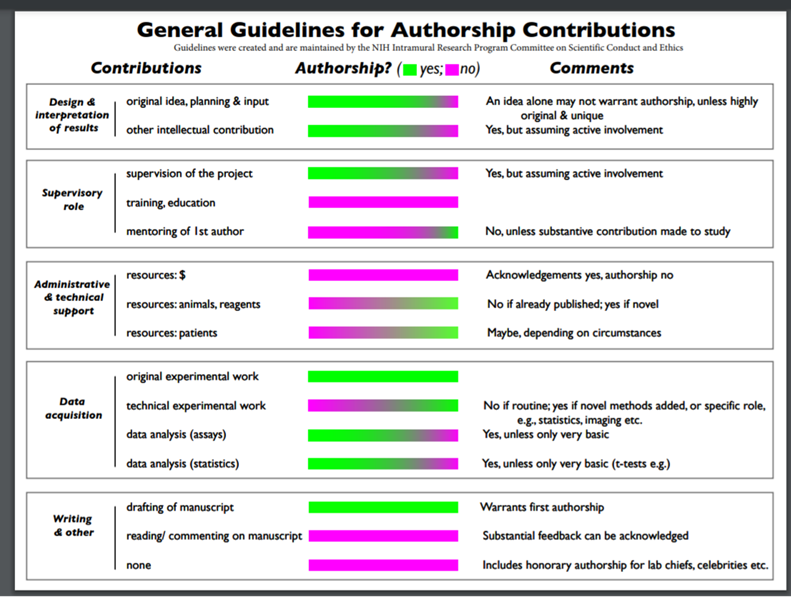

The NIH has also put forward its authorship eligibility rules, which come in the form of the following graphic.[57] This graphic visually demonstrates the crucial characteristics of an author while also leaving sufficient leeway for attributing authorship in relatively unusual situations:

CRediT taxonomy

A subject that can raise very heated emotions in a research group is the order of the researchers in the authorship line of a paper. It is convention that the first author (often a junior researcher) did the most work, the last author is the senior researcher and corresponding author, and the authors in between are ranked according to the perceived weights of their contributions. Adding to the squabbling that can break out about authorship is that some journals only allow the first three or six authors on a paper to be listed in the bibliography. Thus, competition for the first three authorship places is high, and the resultant disputes can lead to difficult tensions in the research group.[58]

To limit this, and to increase transparency and boost collaboration, the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) was generated. This taxonomy consists of 14 categories: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. The taxonomy requires that each author identifies which of these categories reflect their contributions. The CRediT list is then published in the paper.

The CRediT taxonomy evolved in 2012, when a prototype was established by a small group of journal editors together with Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts) and the Wellcome Trust (London). The taxonomy was then refined under the auspices of the Consortia for Advancing Standards in Research Administration (CASRAI). The current form of CRediT emerged in 2015, was endorsed by the National Academy of Sciences in 2018, and became an American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/National Information Standards Organization (NISO) standard in 2022.[59] CRediT was adopted by the open-access mega publishers Public Library of Science (PloS) and eLife in 2017 and has since then been promulgated by many major publishers, including Elsevier, Wiley, Cell Press, Springer, and Oxford.[60]

It should be noted that the CRediT categories include contributions that do not meet the ICMJE threshold for authorship (e.g. Funding Acquisition). Therefore, at this time, CRediT should be seen as an adjunct to ICMJE recommendations. It does not designate the right to authorship, it only delineates in more specific terms the contributions of the authors on the paper.

Uptake of authorship guidelines

The current authorship guidelines thus make it clear that a researcher should have made substantial intellectual contributions to a paper to be considered an author. The activities that do not qualify for authorship have also been delineated. However, although the core elements of the most well-known and broadly endorsed rules – those of the ICMJE – were first published in 1985 and have been adopted by most reputable publishers and journals, the guidelines are still relatively poorly known, and training of established researchers and juniors remains limited. For example, only 34% of 3,859 authors of 2014 BMJ articles said their institution had an authorship policy, and a quarter of these respondents were not “very familiar” with ICMJE authorship criteria despite being corresponding authors.[38] Several recent country-specific reviews also report that 70% of health-science college students did not know the policy of their institution regarding authorship,[61] and only a quarter of health-science faculty members were aware of ICMJE guidelines.[62]

Conclusion

Authorship on scientific research papers can endow many professional and monetary rewards, but with these advantages come the responsibility to behave ethically. To safeguard the integrity of the scientific literature and promote ethical and productive biomedical research, clear authorship guidelines have been developed and widely disseminated in the last decade. It is vital that all researchers and their institutions become fully cognizant of these guidelines and follow them not only to their letter but also their spirit. This is to their advantage as well, because research misconduct is broadly considered to be “behavior by a researcher, intentional or not, that falls short of good ethical and scientific standards”,[63] and there can be serious professional and personal consequences of behaving unethically in science.

References

1. Buckwalter JA, Tolo VT, O’Keefe RJ. How do you know it is true? Integrity in research and publications: AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97: e2. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.00245

2. Marret E, Elia N, Dahl JB, McQuay HJ, Møiniche S, Moore RA, et al. Susceptibility to Fraud in Systematic Reviews. Anesthesiology. 2009;111: 1279–1289. doi:10.1097/aln.0b013e3181c14c3d

3. White PF, Kehlet H, Liu S. Perioperative analgesia: What do we still know? Anesth Analg. 2009;108: 1364–1367. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a16835

4. Fanelli D. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS One. 2009;4. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005738

5. Integrity TO of R. Handling Misconduct - Complainant. [cited 28 Feb 2025]. Available: https://ori.hhs.gov/whistleblowers

6. Office of Inspector General UD of H and HS. Duke University Agrees to Pay U.S. $112.5 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations Related to Scientific Research Misconduct. 2019. Available: https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/duke-university-agrees-to-pay-us-1125-million-to-settle-false-claims-act-allegations-related-to-scientific-research-misconduct/

7. de Viron S, Trotta L, Schumacher H, Lomp H-J, Höppner S, Young S, et al. Detection of Fraud in a Clinical Trial Using Unsupervised Statistical Monitoring. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022;56: 130–136. doi:10.1007/s43441-021-00341-5

8. Thiese MS, Walker S, Lindsey J. Truths, lies, and statistics. Journal of thoracic disease. China; 2017. pp. 4117–4124. doi:10.21037/jtd.2017.09.24

9. Bradshaw MS, Payne SH. Detecting fabrication in large-scale molecular omics data. PLoS One. 2021;16: e0260395. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260395

10. Collier R. Shedding light on retractions. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. Canada; 2011. pp. E385-6. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3827

11. Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. Fraud and plagiarism: Important problem in scientific publication. Med Journal, Armed Forces India. 2016;72: 304–307. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2016.06.010

12. Zimba O, Gasparyan AY. Plagiarism detection and prevention: a primer for researchers. Reumatologia. 2021;59: 132–137. doi:10.5114/reum.2021.105974

13. Mayo-Wilson E, Li T, Fusco N, Bertizzolo L, Canner JK, Cowley T, et al. Cherry-picking by trialists and meta-analysts can drive conclusions about intervention efficacy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91: 95–110. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.07.014

14. Rao KN, Mair M, Arora RD, Dange P, Nagarkar NM. Misconducts in research and methods to uphold research integrity. Indian J Cancer. 2024;61: 354–359. doi:10.4103/ijc.ijc_4_23

15. Andrade C. HARKing, Cherry-Picking, P-Hacking, Fishing Expeditions, and Data Dredging and Mining as Questionable Research Practices. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82. doi:10.4088/JCP.20f13804

16. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR): Reporting guidelines. [cited 2 Mar 2024]. Available: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/

17. Sanderson K. Science’s fake-paper problem: high-profile effort will tackle paper mills. Nature. England; 2024. pp. 17–18. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-00159-9

18. Else H, Van Noorden R. The fight against fake-paper factories that churn out sham science. Nature. England; 2021. pp. 516–519. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00733-5

19. Lowe D. Just Bribe Everyone - It’s Only the Scientific Record. In: Science [Internet]. 2024 [cited 3 Mar 2024]. Available: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/just-bribe-everyone-it-s-only-scientific-record

20. Frank F, Florens N, Meyerowitz-Katz G, Barriere J, Billy É, Saada V, et al. Raising concerns on questionable ethics approvals - a case study of 456 trials from the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire Méditerranée Infection. Research integrity and peer review. England; 2023. p. 9. doi:10.1186/s41073-023-00134-4

21. Ferris LE, Winker MA. Ethical issues in publishing in predatory journals. Biochem medica. 2017;27: 279–284. doi:10.11613/BM.2017.030

22. Alvarado-de-la-Barrera C, Reyes-Terán G. How to Avoid Predatory Publishing. Rev Invest Clin. 2020;73: 006–007. doi:10.24875/RIC.20000221

23. How to spot dodgy academic journals. The Economist. 2020. Available: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/05/30/how-to-spot-dodgy-academic-journals

24. Keeler A, ElHawary H, Tuen YJ, Courtemanche R, Gilardino MS, Arneja JS. The Presence of Predatory and Open Access Journal Publications Among Canadian Plastic Surgery Residency Applicants. Plast Surg (Oakville, Ont). 2024; 22925503241300336. doi:10.1177/22925503241300336

25. Ángeles Oviedo-Garciá M. Journal citation reports and the definition of a predatory journal: The case of the Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). Res Eval. 2021;30: 405–419. doi:10.1093/reseval/rvab020

26. Zevering Y. Deceptive (predatory) journals. 2018 [cited 28 Jan 2025]. Available: https://www.scimeditor.com/deceptive-predatory-journals

27. Memon AR. Revisiting the Term Predatory Open Access Publishing. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34: e99. doi:10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e99

28. Frandsen TF. Authors publishing repeatedly in predatory journals: An analysis of Scopus articles. Learn Publ. 2022;35: 598–604. doi:10.1002/leap.1489

29. Schofferman J, Wetzel FT, Bono C. Ghost and guest authors: you can’t always trust who you read. Pain Med. 2015;16: 416–420. doi:10.1111/pme.12579

30. Picano E. Who is the author: genuine, honorary, ghost, gold, and fake authors? Explor Cardiol. 2024;2: 88–96. doi:10.37349/ec.2024.00024

31. Staff report on Medtronic’s influence on INFUSE clinical studies. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2013;19: 67–76. doi:10.1179/2049396713Y.0000000020

32. McHenry LB. The Monsanto Papers: Poisoning the scientific well. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2018;29: 193–205. doi:10.3233/JRS-180028

33. Rivera H. Coercion Authorship: Ubiquitous and Preventable. J Korean Med Sci. 2024;39: 1–5. doi:10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e215

34. da Graca B, Pollock BD, Phan TK, Carlisi C, Gonzalez Peña TI, Filardo G. Female-Authored Articles Are More Likely to Include Methods-Trained Authors. Mayo Clin proceedings Innov Qual outcomes. 2019;3: 35–42. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.11.001

35. Reisig MD, Holtfreter K, Berzofsky ME. Assessing the perceived prevalence of research fraud among faculty at research-intensive universities in the USA. Account Res. 2020;27: 457–475. doi:10.1080/08989621.2020.1772060

36. Goddiksen MP, Johansen MW, Armond AC, Clavien C, Hogan L, Kovács N, et al. “The person in power told me to”-European PhD students’ perspectives on guest authorship and good authorship practice. PLoS One. 2023;18: 1–27. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280018

37. Picciariello A, Dezi A, Altomare DF. Undeserved authorship in surgical research: an underestimated bias with potential side effects on academic careers. Updates Surg. 2023;75: 1807–1810. doi:10.1007/s13304-023-01581-w

38. Schroter S, Montagni I, Loder E, Eikermann M, Schäffner E, Kurth T. Awareness, usage and perceptions of authorship guidelines: an international survey of biomedical authors. BMJ Open. 2020;10: e036899. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036899

39. Abrahams M. Man at work: Spreading the word about Struchkov. the Guardian. 2008. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2008/mar/11/highereducation.research

40. The Lancet. The role and responsibilities of coauthors. Lancet. 2008;372: 778. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61315-X

41. Strange K. Authorship: why not just toss a coin? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295: C567-75. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00208.2008

42. Abbott A. Report finds grave flaws in urology trial. Nature. England; 2008. p. 922. doi:10.1038/454922a

43. Kwok LS. The White Bull effect: abusive coauthorship and publication parasitism. J Med Ethics. 2005;31: 554–556. doi:10.1136/jme.2004.010553

44. Tarnow E. The Authorship List in Science: Junior Physicists’ Perceptions of Who Appears and Why. Science and Engineering Ethics. 1999. doi:10.1007/s11948-999-0061-2 4

5. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors. [cited 3 Mar 2025]. Available: https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html

46. Siebert M, Gaba JF, Caquelin L, Gouraud H, Dupuy A, Moher D, et al. Data-sharing recommendations in biomedical journals and randomised controlled trials: an audit of journals following the ICMJE recommendations. BMJ Open. 2020;10: e038887. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038887

47. Koizumi S, Ide K, Becker C, Uchida T, Ishizaki M, Hashimoto A, et al. Research integrity in Instructions for Authors in Japanese medical journals using ICMJE Recommendations: A descriptive literature study. PLoS One. 2024;19: 1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0305707

48. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE. Journals stating that they follow the ICMJE Recommendations. [cited 3 Mar 2025]. Available: https://www.icmje.org/journals-following-the-icmje-recommendations/

49. Ali MJ. No room for ambiguity: The concepts of appropriate and inappropriate authorship in scientific publications. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69: 36–41. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2221_20

50. World Association of Medical Editors (WAME). [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://wame.org/aboutus

51. Winker MA, Ferris LE, Aggarwal R, Barbour V, Callaham M, Cress PE, et al. Promoting Global Health: The World Association of Medical Editors Position on Editors’ Responsibility. The international journal of occupational and environmental medicine. Iran; 2015. pp. 125–127. doi:10.15171/ijoem.2015.638

52. World Association of Medical Editors (WAME). Authorship. [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://www.wame.org/authorship

53. Yonseu Medical Journal. Information for Contributors. [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://eymj.org/index.php?body=instruction

54. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions. Instructions to Authors. [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://www.jeehp.org/authors/authors.php?year=2017_1

55. Flotemersch JE, Rhodus J. Authorship guidance in a federal research laboratory: A case study. Sci Ed. 2016;39: 1–10.

56. Snyder GP, Blalock E, Scott-lichter D, Kahn M, Blume M, Mahar J, et al. CSE ’ s White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal 2009 Update. 2009. Available: http://www.seaairweb.info/journal/3.CouncilofScientific-Editors-White-Paper.pdf

57. National Institutes of Health (NIH). General Guidelines for Authorship Contributions. [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://oir.nih.gov/system/files/media/file/2024-07/guidelines-authorship_contributions.pdf

58. Crossley M. How to Avoid Fights About Authorship Order in Scientific Publications. In: Blog: Crossley Lab [Internet]. [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://crossleylab.wordpress.com/2018/01/26/how-to-avoid-fights-about-authorship-order-in-scientific-publications/

59. University College of London Library. CRediT taxonomy. [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/library/research-support/open-access/credit-taxonomy

60. Virtus Interpress. Virtus Interpress has adopted the CRediT Taxonomy toward the author’s contribution to the work. [cited 25 Feb 2025]. Available: https://virtusinterpress.org/Virtus-Interpress-has-adopted-the-CRediT-Taxonomy-toward-the-author-s.html

61. Badreldin H, Aloqayli S, Alqarni R, Alyahya H, Alshehri A, Alzahrani M, et al. Knowledge and awareness of authorship practices among health science students: A cross-sectional study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12: 383–392. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S298645

62. Alshogran OY, Al-Delaimy WK. Understanding of International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Authorship Criteria Among Faculty Members of Pharmacy and Other Health Sciences in Jordan. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2018;13: 276–284. doi:10.1177/1556264618764575

63. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR). Publication of concordat to support research integrity – July 2012. 2012 [cited 3 Mar 2025]. Available: https://www.equator-network.org/2012/01/24/publication-of-concordat-to-support-research-integrity-july-2012/